Why the cold storage market is no longer as hot

The cold storage market has cooled somewhat since our last outlook in 2022. Still dealing with the COVID-led supply/demand disruptions at the time, the market has continued to shift. For one, the boost to the market during COVID from a sudden, large spike in demand from the pharmaceutical sector to store vaccines and supplies has subsided. For another, the strain on Canadian household spending due to inflation the last two years has meant that, for many consumers, fresh food is no longer as viable an option as it was earlier. Sales of canned food are growing.

On the plus side, the market is still strong and growing, supported by merger and acquisition activity as well as new construction projects. And the addition of 2.5 million more people over the last four years, thanks largely to immigration, means more mouths to feed and more storage needed to house the growing stockpiles of food. The same economic drivers that have prompted more canned food purchases are also spurring greater consumption of frozen goods.

Pandemic growth in refrigerated capacity continues post-COVID

The trend we noted in 2022 in the construction of new facilities or refitting existing facilities has continued since then, although perhaps at a slower pace. New build projects and expansions have taken place in Atlantic Canada and the Greater Toronto Area, despite steep, and growing, construction/refitting costs per square foot. Costs vary, depending on location, height of building, racking system, whether it’s a cooler vs. freezer facility, etc., but a realistic range runs from the high $200s to $400+ per square foot. They’re impacted too by the lack of available unimproved land on which to build and customize additional spaces.

Those overhead costs continue to be a burden to entrants new to, or those trying to break into, the cold storage space. Even then, the sector is expected to grow over the short- and long-term, with some industry analysts forecasting between 3.5% and 4.4% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) to 2030 to a value of US$3.1 billion in Canada. The U.S. cold storage sector is expected to grow faster, at a 14.4% CAGR to a value of US$409.4 billion by 2032.

Demand for chilled/cooler space (not frozen) grew during COVID as consumers increased the demand for fresh food, and, while that has continued post-COVID, freezer facilities remain an important space in the overall cold storage market. The biggest boost to the sector comes from the food and beverage sectors, its largest consumers. Growing alongside that are the sectors involved in cold chain logistics (the warehousing and distribution of chilled and frozen goods). This sector is seeing increased demand made possible by developments in preservation techniques and the efficient means of transportation over long distances. That means a lot for a world hungry for more protein and, specifically, animal protein. As more people around the globe shift from a carbohydrate-based diet to one featuring more protein, cold chain logistics will grow in importance.

Global economic upheaval not always reflected in Canada’s trade of perishable foods

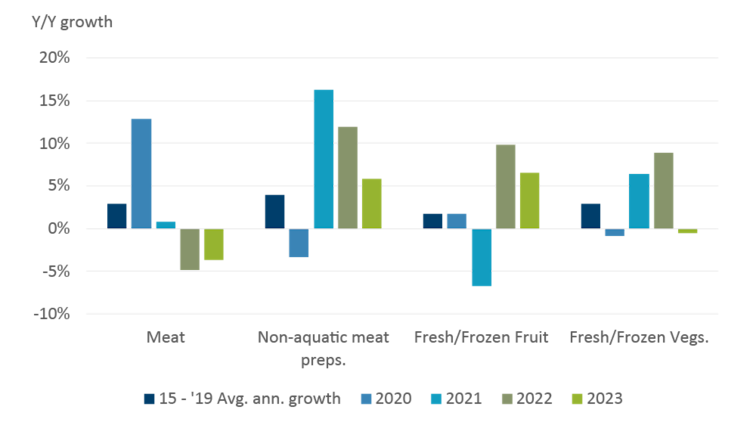

The world reeled in response to the pandemic, with overall trade flows being adjusted, sometimes wildly, both up and down for several individual commodities. For instance, Canadian pork exports to China flourished to record highs in 2020, then dropped quickly year-over-year for the next two years. Slowed global economic growth and supply chain logjams have stymied consumer demand elsewhere but for many Canadian exporters of perishable foods, the post-pandemic period has been one of volume growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Canadian exports of perishable foods subject to some volatility since 2020, but see positive growth overall compared to pre-pandemic trend (kgs)

Source: Statistics Canada

Such growth can perhaps be anticipated with Canada’s added emphasis on setting bold targets to enhance our food exports by 2025, all of which holds implications for the growing need for increased availability of cold storage space.

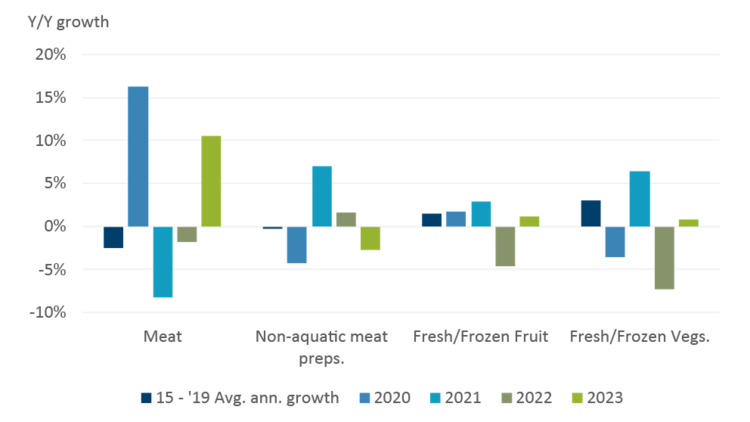

Canada’s imports of perishable foods, (as measured in kilograms) on the other hand, have been much more stable since the start of the pandemic, featuring smaller year-over-year changes for fruits and vegetables, and non-aquatic meat preparations (e.g., sausages and prepared meats). Our meat imports have seen considerably more year-over-year volatility (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The pandemic has spawned large YoY changes in Canada’s meat imports, but other perishable food exports see more stability (kgs)

Source: Statistics Canada

The large year-over-year swings in meat imports and exports of perishable foods seen during and immediately after the pandemic can create uncertainty in a market trying to forecast growth over the next few years. They can also create periods of under- and over-capacity storage utilization.

Bottom line

In response to the slowly cooling demand for cold storage, recent trends in rental lease rates for facilities have somewhat stabilized from the increases witnessed throughout COVID. The sector should see continued growth over the short-term, with higher demand from Canada’s food and beverage sectors driving the growth. While Canada has already far exceeded the goal of agriculture and food exports worth $75 billion set out by the Advisory Council on Economic Growth (a group aimed at making Canada an elite global exporter), there is still ample room to develop export growth by volume. Together with boosts to population growth, the future of Canada’s cold storage space looks bright.

Martha Roberts

Economics Editor

Martha joined the Economics team in 2013, focusing on research insights about risk and success factors for agricultural producers and agri-businesses. She has 25 years’ experience conducting and communicating quantitative and qualitative research results to industry experts. Martha holds a Master of Sociology degree from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario and a Master of Fine Arts degree in non-fiction writing from the University of King’s College.