Export restrictions on the rise – what are the risks and opportunities?

The war in Ukraine is causing many nations to reassess long-established trading relationships, as geopolitical tensions and ag commodity prices continue to rise while grain and oil shipments out of the Black Sea fall. We’re in a new era where trade patterns realign, and food security concerns grow. In response, some nations are reintroducing export restrictions on foodstuffs and inputs necessary to produce them.

Food inflation and food security

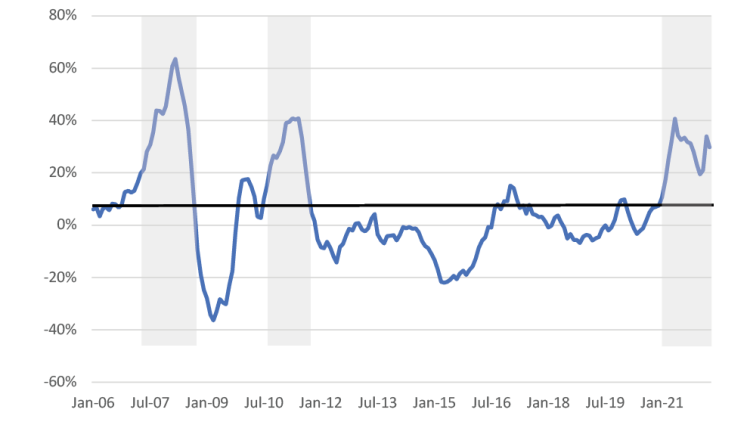

What is driving this increase in export restrictions? The answer is simple: food inflation (Figure 1). During the last two periods when food inflation was this high, we saw political and civil unrest in multiple developing and underdeveloped countries:

In the 2007-08 food crisis, food inflation was above 20% for 16 months and reached a high of 64% in March 2008. The World Food Program estimates 48 countries experienced food riots during this time.

In 2010-11, food inflation was above 20% for 12 months and reached a high of 41% in April 2011. High food costs were a key driving force behind the ‘Arab Spring’ movement of 2011.

Over the past 14 months, food inflation was above 20% and reached a high of 41% in May 2021. It was declining before the war in Ukraine but has been rising again in the last three months.

Figure 1: Global food inflation at the highest level in a decade

Source: FAO Food Price Index.

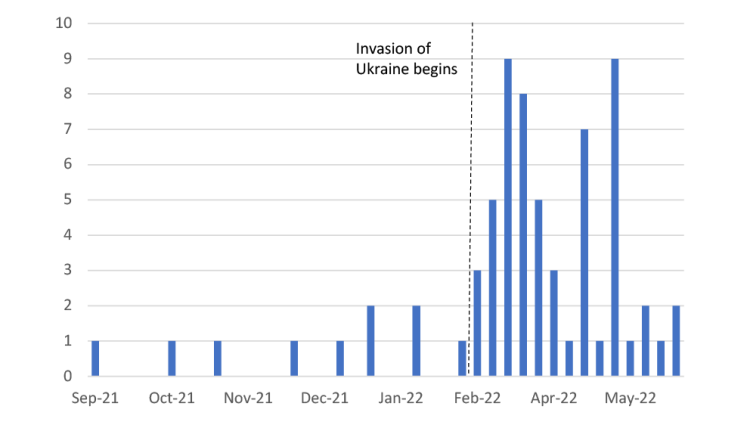

According to the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), 30 countries have introduced export restrictions on food and fertilizer since last fall. These restrictions include bans, taxes, and other methods meant to curb exports, and most of these restrictions occurred after the invasion of Ukraine (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Count of export restriction announcements by week since September 2021

Source: Laborde and Mamun, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Not all restrictions are created equal. Outright export bans and bans by large exporting countries have a bigger impact on global trade and prices.

Vegetable oil market one to watch

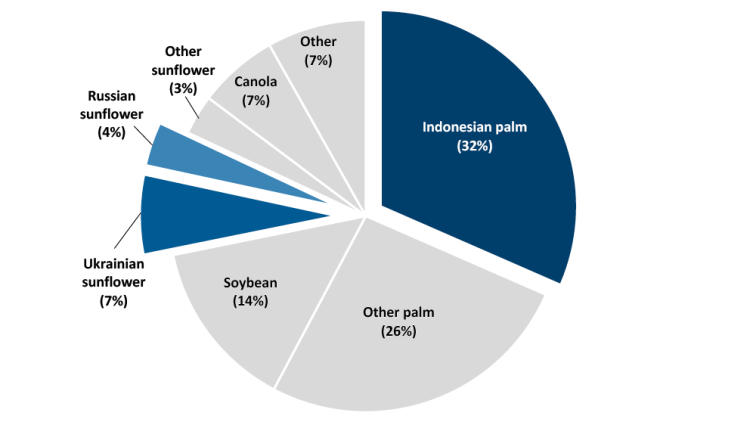

The vegetable oil market is an evolving situation worth monitoring closely. Prices have recently hit record highs. Vegetable oils are a key source of calories worldwide and account for 11% of calories consumed globally. Since 1970, developing countries have tripled their vegetable oils consumption, which has crucially helped reduce calorie shortages.

Notably, 41% of global vegetable oil production is traded, and major exporters have exited the market recently. It began with the war as Ukraine and Russia are the world’s top two exporters of sunflower oil. At the end of April, Indonesia announced a ban on palm oil exports but then three weeks later reversed the ban. This back and forth has a substantial impact as Indonesian palm oil represents 32% of all traded vegetable oil (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The vegetable oil export market is dominated by Indonesian palm oil

Source: USDA PSD.

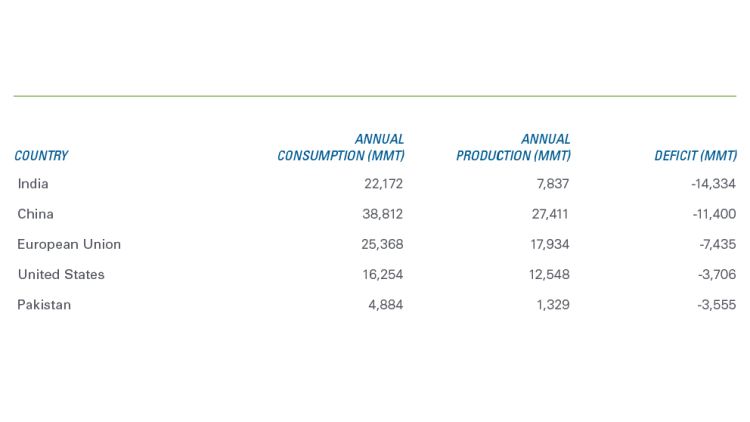

High vegetable oil prices and uncertain trade policies raises important questions: who needs vegetable oil supplies the most, and can they afford them? Some of the largest economies in the world will be the ones driving the bidding war for vegetable oil (Figure 4).

Source: USDA PSD.

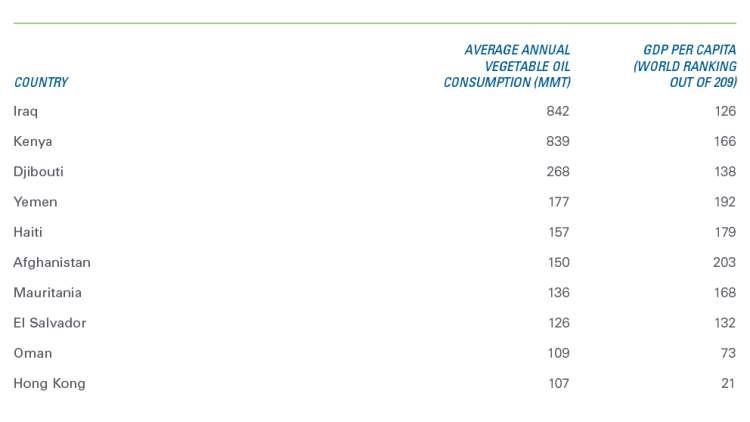

However, multiple countries produce no vegetable oil and rely solely on imports for consumption. They will be the most impacted as prices climb around the globe as these countries can least afford it (Figure 5).

Sources: USDA PSD and the World Bank.

The USDA estimates a strong rebound in vegetable oil supplies for 22-23 from the strong output of soybean oil in the US and South America and canola oil in Canada and the EU. Demand is forecast to rise slower than production, and so ending stocks are projected higher for 22-23.

A similar story is developing in the wheat market, with Russia and Ukraine being large wheat exporters and India limiting exports.

What does it all mean?

Export restrictions can create a vicious cycle – food inflation leading to export bans leading to further food inflation. More export restrictions could be announced if prices continue to rise.

Export restrictions may increase domestic supplies and lower domestic prices, but the evidence is mixed. However, there are costs associated with such policies. Lower prices disincentivize production as they lower domestic producers’ revenues. Globally, export restrictions mean higher world prices. For other countries, especially those with lower incomes, this means increased food insecurity and may create conditions for civil unrest. Reports are emerging that this is already occurring. Developed countries are better positioned to deal with the higher food prices.

Rising protectionism does not usually mean increased opportunities for industries with open borders, such as Canadian agriculture. However, in the case of export restrictions, opportunities exist for large agricultural-producing countries. These opportunities can be short-lived as restrictions will eventually be removed; Indonesia’s stance on palm oil exports is a good example of how quickly policies can change. Assuming logistics can be ironed out and a rebound in production in 2022, there will be no shortage of buyers for Canadian ag commodities this upcoming year. Strong production in 2022 would also go a long way in easing food security concerns.

Senior Economist

Graeme Crosbie is a senior economist at FCC. His focus areas include macroeconomic analysis and insights and monitoring and analyzing Canada’s food and beverage industries. Having grown up on a dairy farm in southern Saskatchewan, he occasionally comments on the health of the dairy industry in Canada.

Graeme has been at FCC since 2013, spending most of that time in risk management. Graeme holds a master of science in financial economics from Cardiff University and is a CFA charter holder.