Farmland values continue to outpace farm income

According to our latest FCC Farmland Values Report, the average value of Canadian farmland increased by 5.2% in 2019. While its appreciation has not reached the double-digit growth rates of 2011 to 2015, farmland affordability continues to decline relative to farm income.

How do you measure affordability?

Affordability is a vague concept if it doesn’t refer to a “standard.” In previous years, we introduced the relationship between the price of farmland and crop receipts. This price-to-revenue ratio measures the value of farmland relative to its ability to generate income.

Price-to-revenue ratio = Average farmland price (per acre) / Average expected receipts (per acre)

Average expected receipts are calculated using expected yields and the average prices producers expect to receive:

Build a representative "standard" crop rotation (e.g., assume a corn/soybeans rotation for Ontario or a canola/wheat rotation for Saskatchewan).

Use each commodity's previous three-year average for prices and yields to estimate expected prices and yields in any given year.

Farmland is becoming less affordable

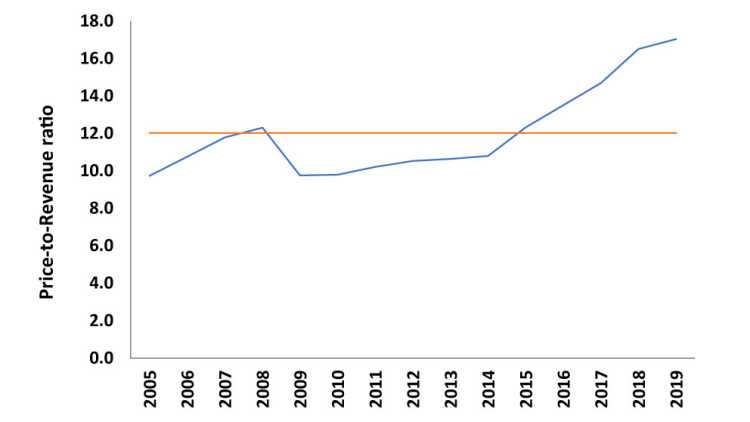

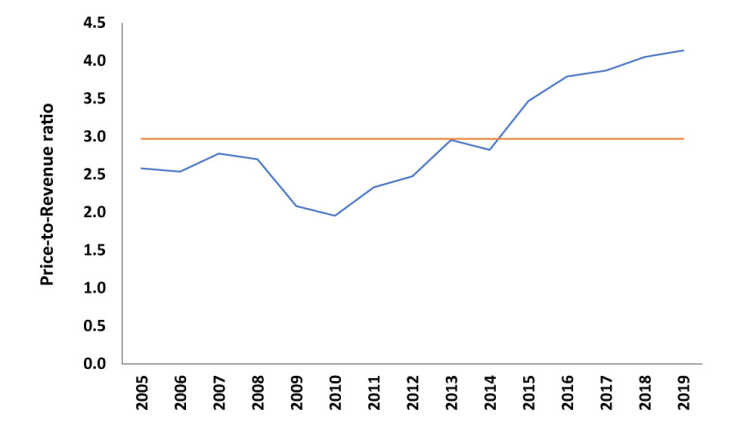

Farmland is getting more expensive relative to income in Ontario (Figure 1) and Saskatchewan (Figure 2). We find a similar situation across most provinces, and 2015 was a turning point. The price-to-revenue ratio crossed its 15-year average following several years of strong revenue growth. And the momentum hasn’t slowed to match the moderation in crop receipts. This resulted in the price-to-revenue ratio reaching an all-time high at the end of 2019.

Figure 1: Average expected price-to-revenue ratio in Ontario

Source: FCC calculations

Figure 2: Average expected price-to-revenue ratio in Saskatchewan

Source: FCC calculations

Farmland more expensive when measured against actual gross revenues

The above ratios were based upon expectations of producers’ revenues. But in any year, poor yields or weaker prices can raise the value of farmland relative to actual revenues.

Recent weather challenges made farmland more expensive when measured against actual gross revenues. The ratio of the average farmland price to actual revenues per acre in Saskatchewan was 4.4 in 2019 vs. 4.1 when using expected revenues.

Using expectations helps to understand the value buyers and sellers assign to farmland based on earning potential. Consecutive years of lower-than-expected revenues may shift the buyers’ willingness to pay for farmland.

What price-to-revenue ratios tell us about future farmland values

Many producers wonder whether farmland values are eventually going to decline. While it can’t be ruled out, it’s unlikely. Farmland appreciation rates are expected to continue slowing down in 2020 as tighter profit margins lower the demand for farmland.

But interest rates are expected to remain low for the foreseeable future, and the supply of available farmland remains quite limited. These factors support the elevated valuation of farmland.

Navigating an uncertain economic environment

We live in unprecedented times. The 2020 economic slowdown due to COVID-19 creates volatility for commodity prices. Demand for commodities may decline with lower consumer income, but prices may also face upward pressures if supply chains are disrupted.

That’s why strategic planning and risk management are important. Use it to:

Stay informed about economic trends.

Estimate what revenues and expenses are likely to be for your operation.

Carry cash flow and working capital analysis under various scenarios.

These actions should inform your strategy for 2020 and highlight potential opportunities.

Leigh Anderson

Senior Economist

Leigh Anderson is a Senior Economist at FCC. His focus areas include farm equipment and crop input analysis. Having grown up on a mixed grain and cattle farm in Saskatchewan, he also provides insights and monitoring of Canada’s grain, oilseed and livestock sectors.

Leigh came to FCC in 2015, joining the Economics team. Previously, he worked in the policy branch of the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture. He holds a master’s degree in agricultural economics from the University of Saskatchewan.