How foreign investment could boost Canada’s exporting superpower

The Advisory Council on Economic Growth has established some far-reaching goals for Canada’s agri-food system, suggesting moves from the world’s 5th-largest to 3rd-largest ag exporter, and from the world’s 11th-largest to 5th-largest food exporter, are possible. The Council also called for Canadian businesses’ increased investment in foreign markets and welcoming more investment from foreign businesses to Canada.

Together, increased exports and foreign direct investment (FDI) can increase Canadian productivity, strengthen our labour force and contribute more to GDP.

But the question for Canadian business is whether these two goals are complementary or should be treated as substitutes. If Canadian businesses invest domestically to increase food exports, how can (or will) our FDI in food processing sectors grow simultaneously?

Why do we need foreign investment?

Canada’s vast agricultural land coupled with a relatively small population makes exporting integral to a successful agri-food supply chain. Canada has reached its status as one the world’s largest agri-food exporters thanks to the productivity gains needed to capitalize on the natural resources we have available.

Export performance is also tied to FDI. Canadian investments abroad (outward FDI) can help to increase Canadian business revenue through affiliate sales in international markets, boosting the competitive strength of companies domestically.

At the same time, foreign companies that invest in Canada (inward FDI) can often extend growth of Canadian exports to foreign markets that were previously inaccessible. They cement good trading relationships and bring knowledge that creates a highly-skilled Canadian labour force – all of which help to build the conditions on which growth in Canada’s future export sales rely.

U.S. investments in Canada’s food processing slow

Foreign investment in Canadian businesses takes one of two forms. Brownfield investors purchase an existing Canadian business. Greenfield investments help build or expand production capacity and can involve sizable infrastructure costs such as construction of new physical assets. They often bring greater benefits to the Canadian economy than do mergers and acquisitions.

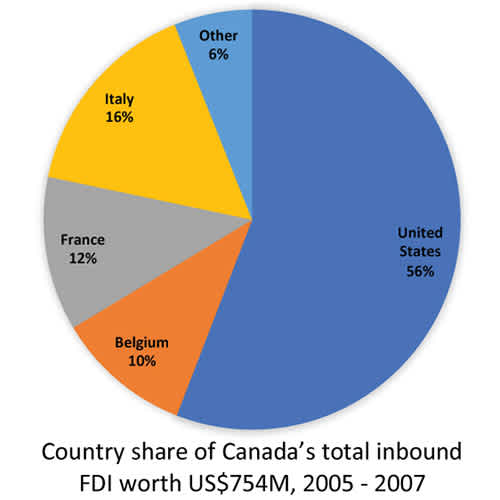

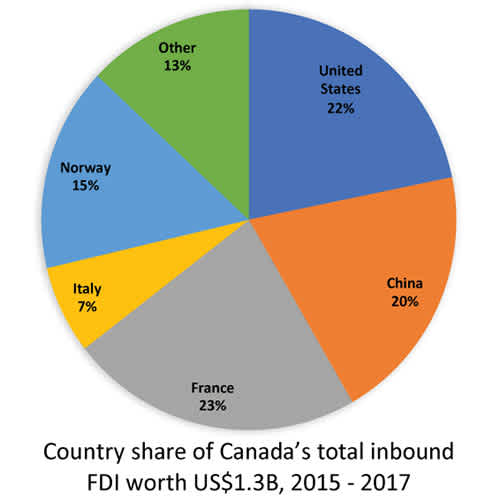

Greenfield investment in Canada has grown and changed over the last 10 years. Between 2005 and 2007, it totalled US$754M and averaged US$34.3 million (M) per investment.

During this period, over half of total greenfield investment in Canada came from the U.S. A decade later however, U.S. investment had declined to 22%. This occurred after total U.S. investments slowed and greenfield FDI from other countries picked up. Total greenfield investments into Canada grew to US$1.3 billion in the 2015-2017 period (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Non-U.S. investment in Canadian business explodes as U.S. investment shrinks

Source: fDi Intelligence and FCC computation

Europe displaced the U.S. as Canada’s largest investor, contributing more than half of all investments in Canada’s food manufacturing sector between 2015 and 2017. That shift occurred on the heels of the free trade negotiations between Canadian and European traders, finalized in the 2014 Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). As European investments in Canadian processors increased, Canadian exports to the EU averaged at least CA$200 million more each year between 2015 and 2017 than in the 2005-2007 period.

With their economic growth prompting a search for business opportunities, Chinese investments in the Canadian food processing sector also increased significantly over that same period, growing to account for 20% of Canada’s greenfield investment between 2015 and 2017. It’s another example of the simultaneous growth of exports and FDI. Canadian food exports to China increased dramatically in that span, averaging CA$40,000 between 2005 and 2007 and CA$362M between 2015 and 2017.

In the 10-year period during which Canadian greenfield investing has increased and its sources diversified, food manufacturing GDP in Canada has also grown – from an average annual rate of 2.1% to an average annual rate of 3.8%.

As Canadian greenfield investing increased and its sources diversified, food manufacturing GDP in Canada grew from an average annual rate of 2.1% to 3.8%.

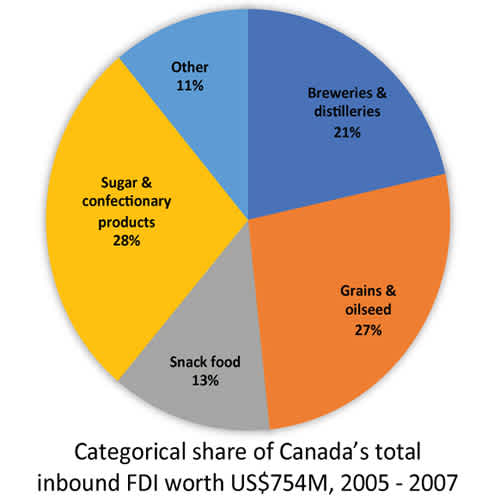

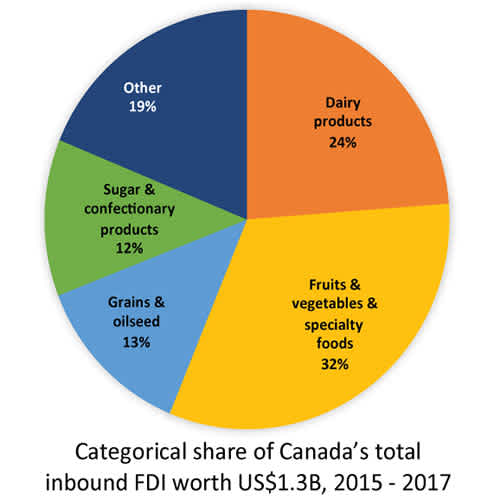

Consumer preferences shape foreign investments

Foreign investors have responded to Canadians’ growing preference for healthier foods with greater greenfield investment since 2005 in the fruit and vegetable processing sector. Technological advances have also helped to change the mix of that investment, with greater variety in value-added products driving up foreign investment in the Canadian dairy sector.

Figure 2: Trends in inward FDI reflect changing food preferences

Source:fDi Intelligence and FCC computation

Canada’s inbound FDI dominated by greenfield investment

Any push to jointly pursue gains in export and FDI performance resulting from the Council’s recommendations may bring even more gains to Canada’s food processing sector in the next decade. Inbound FDI adds economic growth to individual sectors while also enhancing the sector’s domestic competition and lowering retail prices. The last decade has shown simultaneous growth in Canadian food exports and FDI is possible, lending support to the Council’s twinned goals.

The time for such a push is now, though.

Canada is clearly open for business, but our current 2% annual growth in foreign investment lags that of OECD members, which average 7% growth. Moreover, other major food exporters’ greenfield investments represent a higher proportion of their respective total inbound FDI than Canada’s. Given the added benefit it lends export performance, greenfield investment could help achieve the Council’s goals, and a longer-term boost to food processing GDP.

Next week, I’ll look at Canadian outbound FDI and its ties to exports.

Article by: Tyler Betcher, Agricultural Economist

Producers should be mindful that the slowdown in land value growth could increase their risk and that land values must be in synch with variables such as net income, interest rates, commodity prices and productivity, experts say.