How will U.S. tariffs impact Canadian livestock prices?

With Trump returning as U.S. President, Canada and the rest of the world are bracing for the imminent imposition of punitive tariffs. The upcoming tariff shock means Canadian prices are likely to adjust downward, meaning farm cash receipts will be restrained, particularly for livestock producers.

Hogs

Canadian hog producers are highly reliant on U.S. market access, though the dynamics between eastern and western producers deserves some attention. Canada exports 22% of its total hog production, with exports to the U.S. making up 99% of all exports. Of those pigs that are exported, 60% (or 4 million pigs annually) are isoweans weighing less than 7 kgs that are destined for fattening and slaughter in the U.S. The majority (2.6 million) of these isoweans are from Manitoba.

Arguably, U.S. pork processors located in and around Minnesota are the most dependent of any meat processors in the U.S. with respect to unfettered access to Canada’s livestock supply. This would be true in the short-term at least; in the long-term, given the shorter production cycle of pigs (one sow can produce a litter of 12-14 piglets every six months), it’s arguably easier for U.S. producers to fill supply gaps for hogs than it is for cattle as Canadian exports make up only 5% of total U.S. supply.

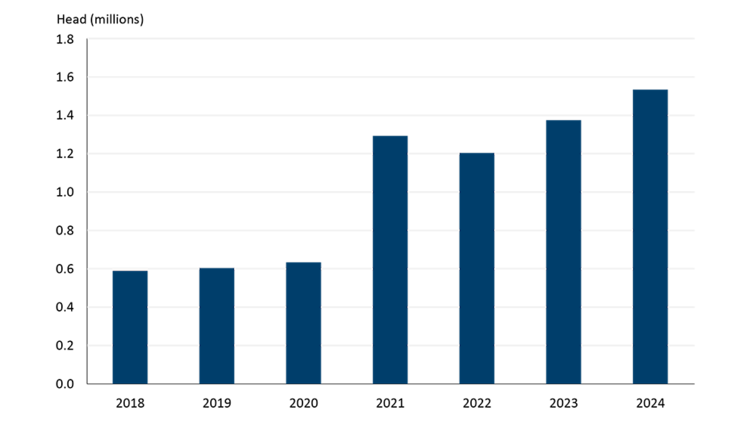

In addition, approximately 25% (or 1.6 million pigs annually) of Canada’s hog exports are market weight hogs destined for slaughter. Over the last four years Canada has lost a significant amount of domestic pork processing capacity; one result of this has been more market-ready hogs have been sent to the U.S. for slaughter, particularly in eastern Canada. In other words, the hog sector’s reliance on access to the U.S. market has grown in the last four years due to plant closures in Canada (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Market-ready hog exports to the U.S. have grown enormously in the last four years

First 10 months of each year

Source: Statistics Canada, FCC Economics

A tariff would likely cause prices to fall. Of course, that would not help hog producers who are just now climbing out of the bottom end of this highly cyclical industry after multiple years of tight and even negative profitability.

Cattle

Canadian cattle producers are also heavily reliant on access to the U.S. market. Canada exports 17% of its total cattle production, with Canadian exports to the U.S. making up 99% of all exports. Of those cattle being sent to the U.S., 70% (or 540,000 head) are destined for slaughter. However, Canadian exports make up only 2% of total U.S. supply.

The frequency of cross border trade is higher in the cattle market. For example, a calf could be born in Alberta, sent to Montana to graze, sent back to Alberta for fattening in a feedlot, and then shipped back to the U.S. for slaughter. This frequency complicates the calculation of potential tariff impacts.

A tariff would likely cause a decline in Canadian cattle prices. Unlike their colleagues in the hog sector, cattle producers, who are currently seeing record-high prices, are in a better position to absorb this shock, although it’s clear that profitability will be negatively impacted.

Graeme Crosbie

Senior Economist

Graeme Crosbie is a Senior Economist at FCC. He focuses on macroeconomic analysis and insights, as well as monitoring and analyzing trends within the dairy and poultry sectors. With his expertise and experience in model development, he generates forecasts of the wider agriculture operating environment, helping FCC customers and staff monitor risks and identify opportunities.

Graeme has been at FCC since 2013, spending time in marketing and risk management before joining the economics team in 2021. He holds a master of science in financial economics from Cardiff University and is a CFA charter holder.