Q1 2024 Macroeconomic snapshot: Comparing Canadian and U.S. economic performance

While interest rates have gone up at about the same pace in the U.S. and Canada, the associated drag on the economy has clearly been more pronounced this side of the border. Just look at what happened last year as Canada’s GDP growth was restricted to 1.1%, well below the 2.5% growth print stateside. The performance gap was entirely due to domestic demand, particularly interest-rate-sensitive components of GDP, namely housing, consumption spending and business investment. And with rates likely to stay elevated for a while, it’s difficult to see Canada making up lost ground on the U.S. in 2024. On the plus side, continued U.S. economic expansion should translate into decent exports for Canadian Ag producers and food and beverage manufacturers.

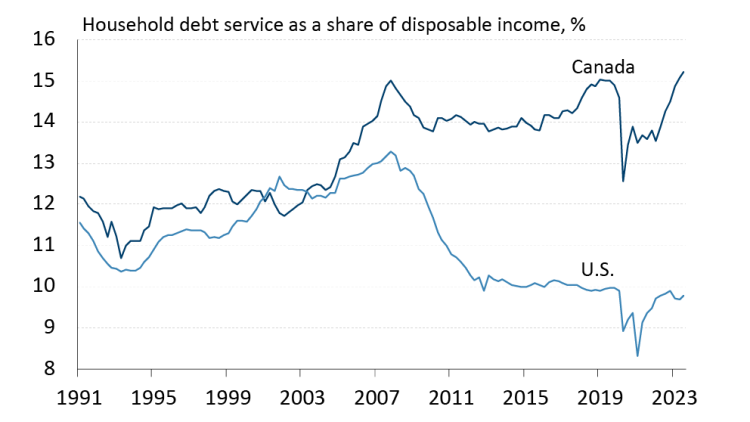

Heavier debt service burden in Canada

Nobody should be surprised that high interest rates bite harder this side of the border. Canadians not only have higher debt loads than Americans but that debt also renews more regularly e.g., mortgage terms in Canada generally do not exceed 5 years while in the U.S. it’s not uncommon to find 30-year mortgages. All of that means that the household debt burden is heavier in Canada.

Note that more than 15% of disposable income goes towards servicing debt in Canada, while in the U.S. the debt service ratio is less than 10% (Figure 1). The debt service burden was similar in both countries back in 2005, but since then there’s been a sharp divergence as the Financial Crisis of 2007/08 (and resulting collapse of the U.S. housing market) prompted massive household deleveraging in America, while Canadians went the other way, piling on debt in synch with a soaring housing market.

Figure 1. Americans bear a much smaller debt service burden than Canadians

Source: Statistics Canada, U.S. Federal Reserve

This higher sensitivity to interest rates (compared to Americans) wasn’t immediately apparent, but it became clearer as rates jumped to multi-decade highs in the post-pandemic era. The surge in rates prompted Canadians to save more (the household savings rate doubled from about 3% prior to the pandemic to 6.2% at the end of 2023), contrasting sharply with the observed drop in the savings rate stateside. And that clearly impacted spending.

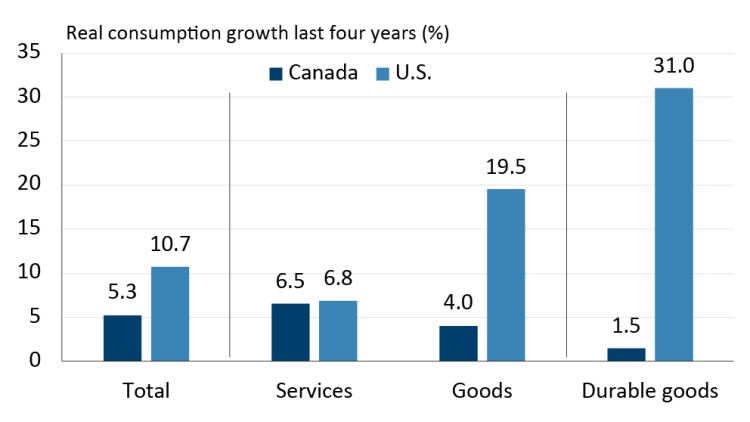

While consumption of services has grown at roughly similar pace in both countries over the last four years, outlays on goods have grown five times slower in Canada compared to the U.S. over that period, restrained by the highly rate sensitive durable goods i.e., long lasting goods such as automobiles, electronics or appliances (Figure 2). This is all the more remarkable considering Canada’s population growth outpaced that of the U.S. over the period. It should also not come as a surprise that per capita spending on food in Canada declined in 2023 while food and beverage manufacturers recorded minimal growth in sales (mostly from strength in a few export markets).

Figure 2. Canadian consumption has underperformed relative to the U.S. over the last four years

Source: Statistics Canada, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

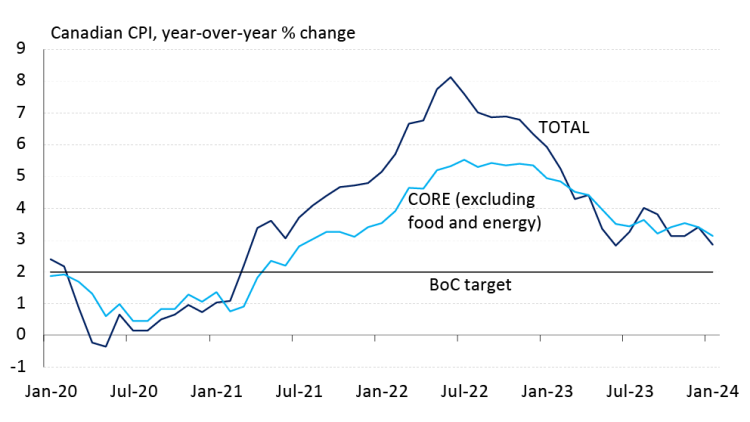

Below-potential growth will take steam out of inflation

Looking ahead, Canadian consumption is likely to continue underperforming relative to the U.S. (although we’re expecting spending growth to moderate stateside as well due to a low savings rate) as the debt service ratio remains elevated amid upcoming mortgage renewals. High housing costs and a weakening labour market are also expected to challenge the consumer this year. Another challenge is the expected deceleration in population growth. So don’t be surprised if consumer spending (i.e., 60% of the economy) and, therefore, real GDP growth tread water again this year.

A second consecutive year of below potential growth should take care of the inflation problem, although not as fast as some are expecting. Core inflation, which excludes volatile items (and is a better gauge of underlying price pressures), is heading down, but very slowly (Figure 3). This persistence in core inflation should not be surprising though given that wages (a major cost that some businesses have been passing on to the consumer) continue to grow well above the pre-pandemic pace. But the expected loosening of the labour market and accompanying rise in the jobless rate should take steam out of wages later this year and give encouragement to the central bank that the downtrend in core inflation is sustainable. That will have important implications for interest rates.

Figure 3. Inflation slowly coming down towards Bank of Canada’s 2% target

Source: Statistics Canada

Implications for interest rates and the dollar

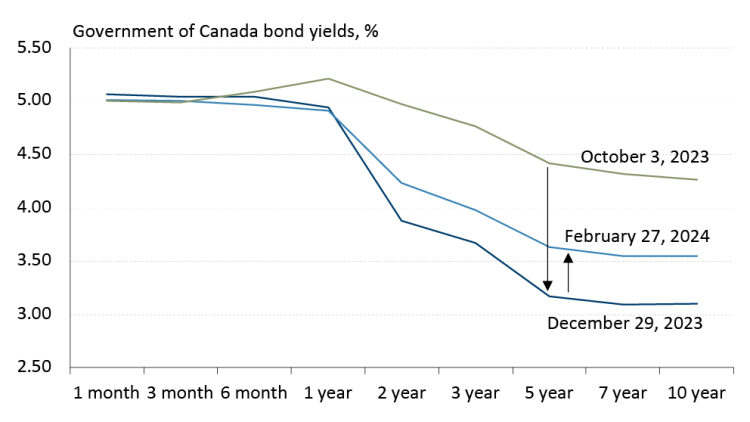

After falling to multi-month lows at the end of 2023, Government of Canada bond yields are now creeping up again across the yield curve (Figure 4). That, of course, came courtesy of a string of economic reports that pointed to inflation persistence. This persistence prompted the Bank of Canada (BoC) to adopt a more hawkish stance than what markets had expected, forcing the latter to push back expectations of interest rate cuts.

As mentioned above, wage growth, and therefore inflation, will moderate later this year as the labour market loses steam in synch with a weakening economy, but it’s a process that will take time to fully unfold. So, while bond yields may rise a bit more over the near term, the longer-term downtrend will resume as inflation falls in a more substantial way later in the year.

Near term yields, which are tied to the BoC’s overnight rate, are likely to remain unchanged for now. The central bank reiterated its message at its March meeting that it was not considering interest rate cuts in light of inflation persistence. In other words, the already-inverted yield curve could get even more inverted over the near term i.e., near term rates stay unchanged while long rates fall. But once the central bank is convinced that the downward trend in inflation is sustainable and starts cutting rates in the second half of 2024 - we currently anticipate a total of 3 rate cuts of 25 bps by end of the year -, look for the yield curve to become less inverted, en route to returning to its normal positive slope.

Figure 4. Canadian yield curve still inverted, but shifting

Source: Bank of Canada

Given this outlook on interest rates, as well as forecasts of soft commodity prices amid weak world GDP growth, one might think that 2024 will be another difficult year for the Canadian dollar. There’s, however, one factor that could allow the loonie to defy the odds. US dollar strength, which has been a feature in global financial markets since the Federal Reserve started to raise interest rates back in March 2022, will eventually fade. And that may happen this year as declining U.S. inflation allows the Fed to start cutting its funds rate. In other words, it’s possible for the Canadian dollar to find some support, even in an environment of sluggish but positive economic growth.

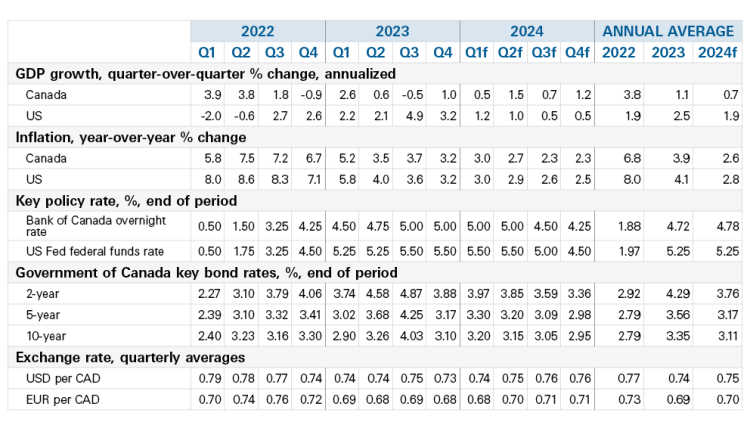

Summary of forecasts of key economic variables

The table below summarizes FCC Economics’ outlook of select economic variables.

Table 1: Forecasts of key economic variables

Source: FCC Economics, Bloomberg

Krishen Rangasamy

Manager, Economics, Principal Economist

Krishen Rangasamy is the Manager, Economics and Principal Economist at FCC. His insights and leadership help guide research on topics related to macroeconomics and agriculture, which FCC and external clients use to support strategy and monitor risk.

Prior to joining FCC in 2023, Krishen spent over fifteen years as a macroeconomic specialist on Bay Street, including at two major Canadian banks, where he advised trading desks and helped lead economic research and forecasting. He also regularly appeared on leading business TV channels and written media with his insightful commentaries on financial markets. Before going into investment banking, Krishen worked as an analyst in the energy industry in Western Canada. Krishen received his master of arts degree in economics from Simon Fraser University.