2021 top economic trends: Red meat export risk and opportunities

COVID-19’s role in changing the world’s supply chains in 2020 can’t be overstated. Testing supply chains everywhere, COVID-19 exposures slowed or shuttered global manufacturing. Consumers consumed differently. The virus and its consequences, like food service shutdowns, turned shoppers into online aficionados as hobbies, home improvements, in-home dining and grocery hoarding assumed new importance.

But other better-known forces also disrupted them. Geopolitical tensions shifted trade balances and important trade relationships while climate change continued to wreak havoc in global agricultural production. The Black Sea region’s extreme dryness and major storms in the U.S. counted among 2020’s examples, reworking the story from Europe and Australia in 2019.

The incremental impacts of climate change over the short term are hard to decipher and harder to forecast for a single year. With that caveat in mind, we believe these three forces will continue to dominate headlines this year as they further shift the world’s supply chains. How they’ll alter risks and opportunities for Canadian production and exports of red meat in 2021 is the subject of this post.

Canada will see more domestic and global red meat buyers in 2021

Many countries can’t produce enough to meet their domestic consumption needs. Japan, for instance, has a large population and tiny land resources. China has much more land but a massive population. As a net exporter of food, Canada produces more beef and pork than we eat. That means opportunities for Canada as a trusted, reliable supplier of high-quality red meat in 2021.

At the same time, COVID fed into a growing swell of “buying local” in 2020, a shift prompted earlier by consumers’ interest in the sources of food supplies. Canadian small businesses have taken the brunt of the economic hit during COVID’s slowdowns and lockdowns, and everywhere, the plea to keep hometown businesses alive has helped support this revolution towards local food.

Therefore, Canadian producers have two opportunities: meeting the needs of domestic consumers who want to source their food locally and, as one of the largest food exporters in the world, meeting the needs of major food importers.

Consumption and production – or how exports are made

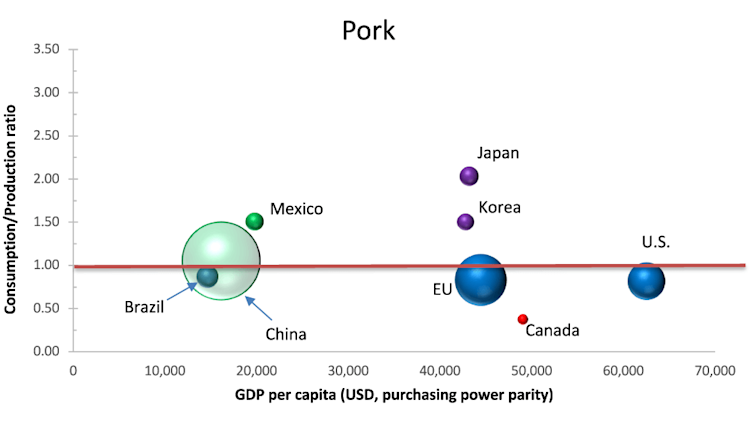

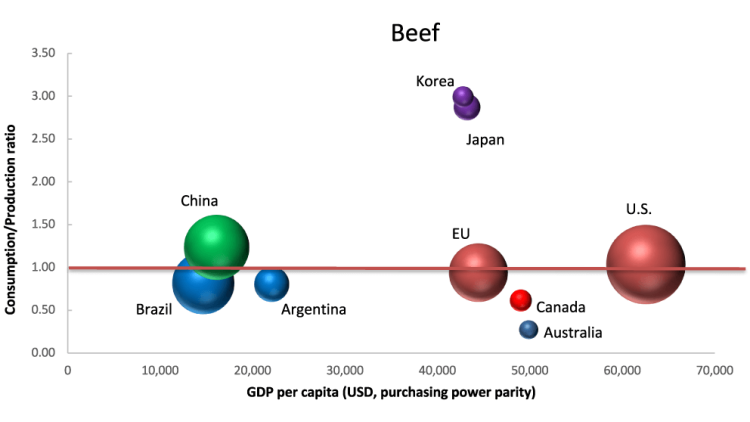

The bubbles in the figures below highlight some of the best global opportunities for Canada. Even as different levels of global supply chains look to source more meat locally, both wealthy and developing countries still rely on imports. The location of each bubble in the charts is based on their supply and demand factors in 2019. Because those factors will change in 2021, the bubbles’ locations will also change.

Figure 1: Will China reduce its pork imports in 2021?

Sources: UN Comtrade, World Bank and FCC calculations. The chart depicts pork production, consumption and GDP in 2019. Japan’s 2019 GDP per capita value sourced from Knoema World Data Atlas. Net pork importers have C/P scores > 1 (above the red line). Net exporters have scores < 1 (below the red line). Consumption (volumes) provides the size of bubble for each country. The chart includes the top 5 importers and/or exporters of pork, with the EU (28) selected instead of individual member countries. Canada is always included, even if not in the top 5.

In 2019, China was a net importer of pork, although not by much (Figure 1). The world’s largest consumer of pork, their own production has usually been sufficient to meet most of their consumption needs. But African Swine Fever, responsible for millions of pigs culled, has boosted their pork imports since 2018. In 2020, they were on track to rebuild their hog/pig herd to pre-ASF levels. A resurgence of COVID and/or ASF that disrupts manufacturing has the greatest potential to hamper those efforts. Should China’s rebuilding efforts succeed however, its bubble will shift downward in the chart, weakening Canada’s opportunity this year.

The ability of the global economy to rebound in 2021 can shift the location of these bubbles. Higher income countries aren’t likely to see consumption shift lower, as food demand in each is quite inelastic relative to income. In lower-wealth countries, it’s different. COVID’s bite out of their GDP will drive reduced consumption of the more expensive red meats. GDP growth would expand the meat demand of these net importing countries.

China assumed an unusual dominance in 2019 as the world’s largest beef importer. Unlike the U.S., which also imports beef, China produces little. Their consumption needs must almost exclusively be found in imports. Should GDP growth there be enough to spur red meat consumption, Canada has a real opportunity to supply the world’s largest market.

Figure 2: While the E.U. and U.S. meet their own needs, China’s demand for beef grows

Sources: UN Comtrade, World Bank and FCC calculations. The chart depicts beef production, consumption and GDP in 2019. Japan’s 2019 GDP per capita value sourced from Knoema World Data Atlas. Net beef importers have C/P scores > 1 (above the red line). Net exporters have scores < 1 (below the red line). Consumption (volumes) provides the size of bubble for each country. The chart includes the top 5 importers and/or exporters of beef, with the EU (28) selected instead of individual member countries. Canada is always included, even if not in the top 5.

Canada currently exports just under half of our beef production, and that’s unlikely to change much in 2021. But our own ability to deliberately shift the location of others’ bubbles this year will depend on the effects of North American climate change and COVID's effects on our manufacturing. Climate change is expected to produce drier, hotter summers on Canadian prairies in the long term, with more flooding in spring and fall and more droughts during growing seasons. The 2020 growing season worked out extremely well for Canadian producers, but the most difficult aspect of climate change is that it’s almost impossible to know where and when it’ll appear globally. Canada’s beef and hog production may see higher prices for feed in 2021.

Why it matters

Global supply chains are still signaling that Canadian exports are important. High-income economies (e.g., Japan, Korea, the U.S. and the E.U.) illustrate the opportunities for wealth to drive imports of Canadian exports. Still, China, given its size, is just as — if not more — important.

Here at home, there’s plenty of potential for pent-up demand to drive red meat consumption growth once we resume pre-pandemic patterns. Foodservice may reopen in 2021, boosting a large component of demand. Plus, the evidence of Canadians’ high savings coupled with low interest rates will also drive consumption higher – a much needed corrective to 2020’s lows.

Next week, we’ll look at prospects for crops.

Economics Editor

Martha joined the Economics team in 2013, focusing on research insights about risk and success factors for agricultural producers and agri-businesses. She has 25 years’ experience conducting and communicating quantitative and qualitative research results to industry experts. Martha holds a Master of Sociology degree from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario and a Master of Fine Arts degree in non-fiction writing from the University of King’s College.