What do tariffs mean for the Canadian dollar?

Only the brave would be optimistic about the Canadian dollar these days. The currency’s depreciation over the past year has been spectacular, from around 75 U.S. cents just twelve months ago to less than 70 cents this week. So, what happened to the loonie, and how will it fare amid tariff-related uncertainties?

U.S. dollar strength

To be fair, the Canadian dollar isn’t the only major currency struggling to get a grip amid U.S. dollar strength. The trade-weighted U.S. dollar index, which is calculated by the Federal Reserve (Fed), and measures the value of the USD relative to other world currencies, is currently at its highest level in over 20 years. The U.S. economy outperformed several of its peers last year, meaning that inflation and therefore the Fed’s interest rates have generally been higher than in other developed economies. This yield advantage attracts foreign capital to America and accordingly boosts the U.S. dollar relative to other major currencies. At the end of January, for example, the policy interest rate was 4.50% in the U.S. and just 3.00% in Canada. The last time Canada’s yield disadvantage was that large was back in December 1997, when the loonie was trading near 70 cents.

Dull outlook for commodity prices

Another known driver of the Canadian dollar, commodity prices, have risen quite a bit over the past year. The Bank of Canada’s commodity price index at the end of January was up about 6% year-over-year. Clearly, the positive effect of commodities on the currency is being dwarfed by the above-mentioned yield disadvantage and USD strength. Going forward, one can expect the U.S. tariffs and likely retaliatory actions by America’s trade partners to further curtail world trade and limit global GDP growth. If history is any guide, a slowdown of global growth should weigh on commodity prices, and therefore on the Canadian dollar.

Soft Canadian economy

Part of the loonie’s woes is due to low confidence about Canada’s economy among foreign investors. The 2025 forecast for real GDP growth, which many analysts, including us, had pegged at a meagre 1.5% or so (i.e., the average of the last couple of years), may now be revised even lower in light of U.S. tariffs. The longer the trade war lasts, the worse will be the GDP hit, increasing the likelihood of a recession, and therefore more aggressive interest rate cuts by the Bank of Canada. Retaliatory tariffs by Canada on the U.S. will make American goods more expensive and, accordingly, reduce Canadian demand for them. As such, our importers are expected to lower their demand for U.S. dollars, which will provide some support to the loonie. But overall, the impacts of tariffs are unambiguously negative for the Canadian currency.

So, there is downside potential for the loonie, at least over the near term. Exporters may see the silver lining of an even weaker currency, as long as they have market access. But if you’re an importer or a business trying to boost productivity using imported machinery and equipment, then further currency weakness won’t help.

When will the tariff drama end?

Back in 2018-2019 it took about eleven months before U.S. tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum and Canada’s retaliatory tariffs were removed. Nobody knows for sure how long the new U.S. tariffs will be in place once they are implemented, but the massive costs associated with the trade war (especially if those tariffs are broad based) will provide incentives to negotiators on both sides of the border to clinch a deal eventually. But in the meantime, uncertainties related to tariffs will be enough to restrain exports temporarily and depress investment. That will only serve to worsen the Canadian economy’s structural problems.

Lagging investment, particularly relative to the U.S., has indeed translated to weak productivity growth, and therefore diminished competitiveness over the last two decades. That, coupled with lack of diversification - more than 70% of our exports still head stateside - has arguably made exporters increasingly dependent on a depreciating Canadian dollar (versus the USD) to boost sales.

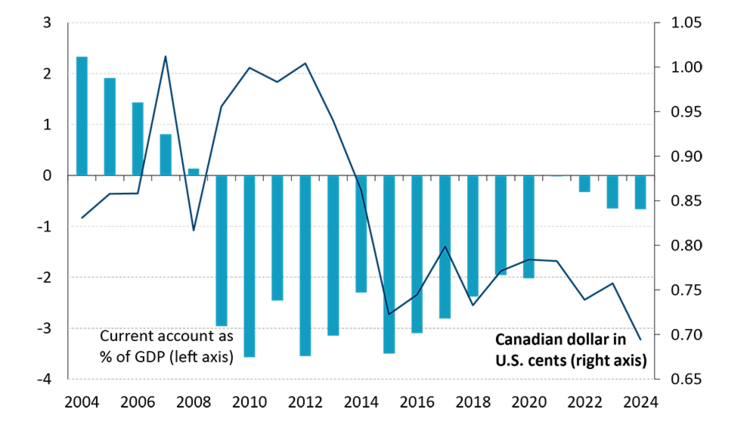

Last year, even with a sinking loonie, the country registered a sixteenth consecutive annual deficit on the current account, the broadest measure of trade (Figure 1). That contrasts sharply with the solid current account surpluses that were generated from 2004-2007 despite the strong loonie, the latter averaging roughly 85 U.S. cents over that period. Simply put, the Canadian dollar’s current woes aren’t just about ongoing cyclical factors. So, while one can expect the loonie to rebound somewhat once the tariff drama is over, don’t expect a return to 85 U.S. cents anytime soon.

Figure 1: Sinking Canadian dollar has not helped restore trade surplus

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC calculations

Manager, Economics, Principal Economist

Krishen Rangasamy is the Manager, Economics and Principal Economist at FCC. His insights and leadership help guide research on topics related to macroeconomics and agriculture, which FCC and external clients use to support strategy and monitor risk.

Prior to joining FCC in 2023, Krishen spent over fifteen years as a macroeconomic specialist on Bay Street, including at two major Canadian banks, where he advised trading desks and helped lead economic research and forecasting. He also regularly appeared on leading business TV channels and written media with his insightful commentaries on financial markets. Before going into investment banking, Krishen worked as an analyst in the energy industry in Western Canada. Krishen received his master of arts degree in economics from Simon Fraser University.