Breaking barriers: Women in Canadian agriculture

Women play a critical role in Canadian agriculture but also face significant participation barriers. Lack of resources and lack of recognition lead to under-representation among farm operators and in leadership roles within agriculture businesses and organizations. The growing skills gap across the agriculture sector makes it imperative to grow gender equity and lift women’s participation in all aspects of farming.

We estimate that achieving revenue equity – with female farm operators earning on average revenues in line with male farm operators – would add an additional $5 billion to agriculture's GDP contribution. Achieving gender parity in the number of farm operators would magnify these economic benefits. Recognizing existing contributions of women could attract more women to the industry, which itself is a function of elevating the status of women’s contributions equal to men’s. We estimate that almost 88,000 additional female farm operators will need to be counted to achieve gender parity by 2026 – 75% of which are already farming but unrecognized as operators, and 25% of which will need to be new entrants.

The status of women in agriculture today

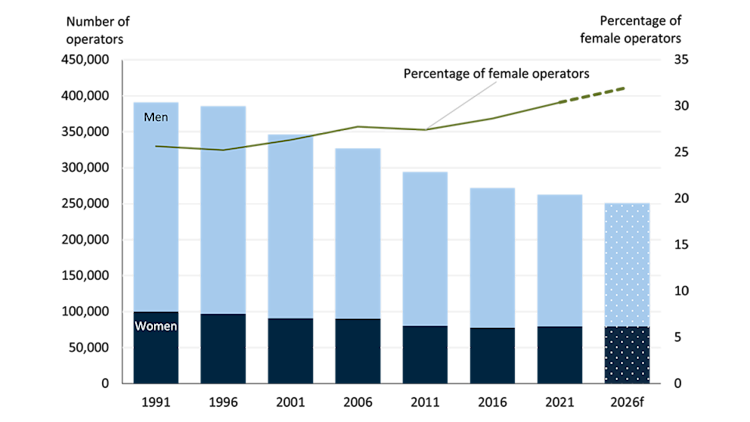

In the 30-year period spanning 1991 to 2021, the percentage of female farm operators in Canada increased from 25.7% to 30.4% (Figure 1). This upward trend is expected to continue, with the proportion of female farm operators expected to reach 31.1% by 2026. While encouraging, it’s important to note that this trend is largely explained by men leaving the industry not by more women joining. Farm consolidations and an aging farm population have reduced the total number of farm operators across Canada over time, with the number of men falling faster than the number of women. So, while the proportion of women farmers has been steadily on the rise, the actual number of women in farming has not been growing by much. In fact, between 2016 and 2021 the number of female farm operators grew for the first time since 1991, but only by 2.5% – translating to less than 2,000 additional farm operators. And women are also still less likely than men to be the sole decision-maker on the farm.

Figure 1: Gender breakdown of farm operators in Canada – women and men, 1991-2026f1

1f=forecasted

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC calculations.

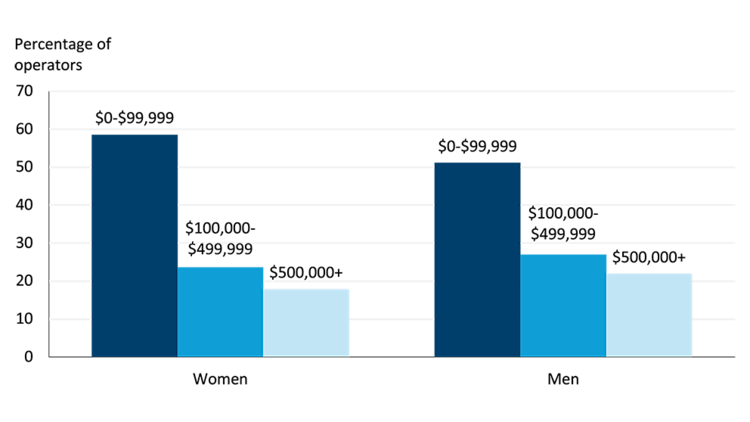

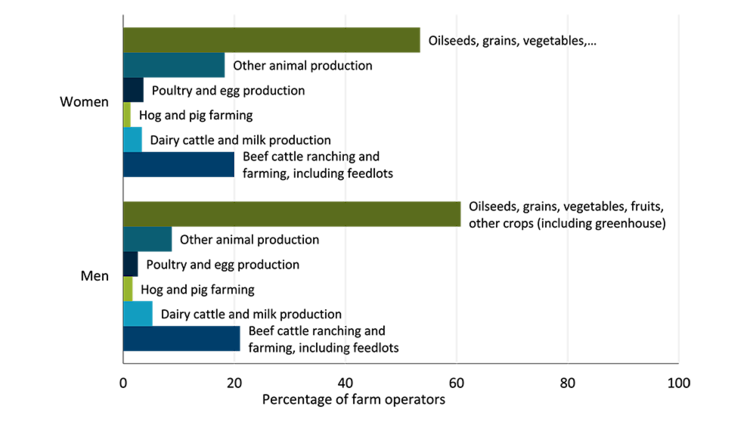

Female farm operators face very different economic circumstances than male farm operators. Female operators tend to have smaller operations, and lower farm incomes. The median farm operating revenue bracket is the same for both men and women, at $50,000 – $99,999 (Figure 2). But approximately 58.6% of female farm operators work on farms that reported less than $100,000 in revenues, compared to 51.1% of male farm operators, based on the most recent census data from 2021. Conversely, only 17.9% of female farm operators were employed on farms with revenues of $500,000 or more, compared to 21.9% of their male counterparts. Women have gained some ground in recent years in high value markets for products like beef, poultry, and eggs. Men continue to dominate the grains and oilseeds market (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Total farm operating revenues for women and men – Canada, 2021

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC calculations.

Figure 3: Types of farms operated by women and men – Canada, 2021

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC calculations.

In their own words: Barriers faced by Canadian women in agriculture

In the fall of 2024, FCC interviewed women working in Canada’s agriculture sector to learn about their experiences. Overall, these producers felt that things are slowly changing for the better. Yet, women still face barriers to full participation in farming.

1. Industry gender norms

The public still expects farmers to be male. Stereotypically, in many farm families the man is labelled as the “farmer”, while the woman is labelled a “farm wife”. Girls growing up in farm families may not feel encouraged from participating in the more operational aspects of farming. This early socialization can shape how women perceive their roles on the farm, and their confidence in engaging in all aspects of farming as adults. Women also tend to be expected to take on more household and childrearing responsibilities and often provide economic stability for their families through off-farm employment, making it more difficult to engage in production work.

2. Devaluation of women’s knowledge, skills and contributions

Women reported that they often feel like they must prove that they are as knowledgeable, skilled, and capable as their male counterparts, and often feel judged to be less competent because of their gender. And that non-production roles dominated by women – like accountant, or finance manager – are often deemed not as important as operational roles that tend to be male dominated.

3. Resource accessibility

Men are more likely to inherit the farm over women, as tradition dictates that these resources be passed from fathers to sons. Women are often excluded from succession planning, and in large part are still expected to marry in to farm families if they want to participate in farming.

4. Physical barriers

Many aspects of farming were not designed with women in mind. For example, most farm equipment has been tailored to the male physique, and these design limitations can make it more difficult for women to engage in the physical side of farming.

5. Lack of representation

Many women shared that their views on their own potential were shaped by what they saw represented as they grew up – which typically was men as decision makers on the farm, and women in supportive roles. A lack of representation of female leadership in agriculture can make it difficult for younger women to feel confident that they can take on leadership roles.

6. Lack of networks and support

Women in farming are more isolated than their male counterparts, and have less access to networking, mentorship, and support. As agriculture continues to be a male-dominated industry, most executive and board positions within agriculture continue to be held by men. Women generally have less access to a network of like-minded peers sharing similar struggles who they can lean on for support and advice, and often have the experience of being the only woman in the room. This can be both challenging and intimidating. Women also face barriers to attending in-person networking events, as they are often juggling childcare and off-farm work.

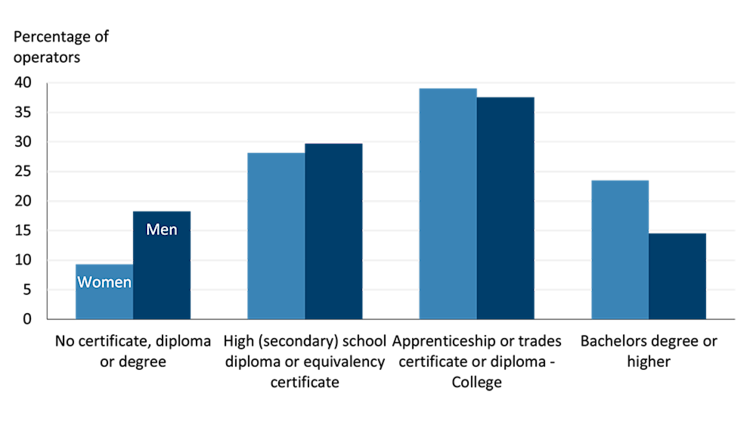

Women are well positioned to be future leaders in Canada’s food system

The labour needs of Canada’s agriculture sector are changing. In this era of digital agriculture and data-driven decision-making, there is a growing need for highly skilled farm labour. Reflecting this need, there has been an overall upward trend in educational attainment in the agriculture labour force in recent years – with a declining number of workers having no formal qualifications, and an increasing number of workers with college and university degrees. This trend is even more pronounced for women, who are more likely to be highly educated than their male counterparts. In 2021, nearly one-quarter (23.5%) of female farm operators possessed at least a bachelor's degree, compared to only 14.5% of male farm operators (Figure 4). And the proportion of female farm operators without any formal education was only 9.3%, notably lower than the 18.2% observed among male farm operators. The current gap in educational attainment between female and male farm operators is greatest for operators aged 30-39; within this age cohort, 36% of women have a university education, compared to only 17% of men.

Figure 4: Educational attainment of farm operators in Canada – women and men, 2021

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC calculations.

A high level of educational attainment makes it easier for women to take advantage of new tools and technologies of farming as they emerge. Many of these innovations are making it easier to overcome some of the physical and social barriers that women in agriculture have faced in the past. A growing number of female farm operators are adopting new production technologies – things like automatic guidance steering, and GIS. These tools can make it easier for women to achieve work-life balance. Women who are highly educated are also well positioned to be thought leaders and champions of the agriculture industry, playing a leadership role beyond the farm level.

Women working in agriculture also continue to demonstrate a strong entrepreneurial spirit, leveraging their skills and expertise to enhance the value of what they produce. Women have been driving the emerging trend of direct to consumer sales of farm goods, with farms run exclusively or jointly by female operators being much more likely to adopt this marketing strategy. And there are a growing number of women working on farms producing organic goods, and using sustainable energy sources and technologies. Women are also carving out space for themselves in growing niche markets, like sheep and goat production.

Achieving gender equity in Canadian agriculture: Some possible steps forward

There is a lot of work that needs to be done to achieve gender equity in Canadian agriculture. Currently we fall behind wholesale and retail, finance, education, health care, and several other industries in terms of women’s participation. Women in agriculture today are highly educated and driven, with strong business acumen. They are well equipped to foster innovation and accelerate new methods, tools, and technologies on the farm. At a time when productivity growth in Canadian agriculture is stagnating, leveraging their skills and entrepreneurial spirit will reap significant economic benefits.

Here are some potential strategies to consider:

Increase the visibility of women in agriculture. Recognizing the important work that women are already doing on farms and in boardrooms across Canada is critical.

Enhance mentorship and networking opportunities. This will help to reduce isolation and build community for women navigating the agriculture and food space. Programs like AgriMentor, that pair new and established women farmers with experienced mentors, and events like Advancing Women Conferences, can foster useful connections for women, helping to address time and cost barriers women often face when engaging in networking. Virtual initiatives can also help to make networking more accessible. The National Women in Agriculture and Agri-Food Network Project is one example of a growing network that connects women in farming through both in-person and virtual initiatives.

Ensure that women have equal opportunity to take on leadership roles. This requires not only reducing gender bias in promotion and hiring, but also ensuring women are supported in stepping into leadership roles when the opportunity arises, through access to things like flexible work arrangements and childcare accommodations.

Improve access to resources. Women have historically been excluded from succession planning and equal access to land and capital. Programs that support women in accessing the resources they need to start their farm businesses are essential moving forward. FCC’s Women Entrepreneur Program is one example of this. A broader cultural shift toward including women in succession planning is also needed to break this inter-generational cycle of exclusion. We are slowly seeing progress in this area, with more women being involved in farm transition planning.

Embracing the strengths and potential of women in agriculture can unlock $5 billion in economic benefits for the agriculture sector. Achieving gender equity can drive innovation, improve productivity, and foster sustainability, leading to a more resilient and prosperous agricultural industry. Together, we can cultivate a future where everyone can contribute and thrive, creating a dynamic and inclusive farming community that benefits all.

Article by: Bethany Lipka, Business Intelligence Analyst, and Isaac Kwarteng, Senior Economist