2024 Farmland rental rates – Renting or purchasing depends on many factors

For the past five years, FCC has been closely monitoring Canadian farmland rental rates and examining the impact of farmland value growth on these rates. According to the FCC Farmland values report, there was a significant increase of 9.3% in average farmland values in 2024. While this growth rate is slower compared to recent years, it remains notably high. In contrast, the trends in cash rental rates have been more moderate. Over the last five years, the Canadian rent to price ratio has fluctuated from 2.70% in 2020 to 2.50% in 2024.

Renting land is an important business decision to manage financial risk. The duration, conditions and options negotiated when renting land has a large impact on the rental market trends. This can lead to rental agreements lagging farmland value changes in the short term.

Rent to price ratio analysis

While there are different kinds of rental agreements used in the agriculture sector, like crop sharing; this analysis focuses on cash rental agreements, which is measured as follows:

The national average RP ratio in 2024 was 2.50%, very similar to the previous year’s rate of 2.52% (Table 1). No rates are published for British Columbia as data in multiple regions of that province were deemed insufficient to provide an accurate average RP ratio.

Table 1: 2024 Rent to price ratio by province, with minimum and maximum range by province, including RP ratio since 2020

Source: FCC

Saskatchewan and New Brunswick saw no change in the RP ratio for 2024, despite strong increases in farmland value in the same period. Rental markets in these provinces quickly adjusted to reflect changes in farmland values. Other provinces showed slower responses, with little or no change in dollars per acre rental rates resulting in a lower RP ratio.

Renting has improved annual cash flow over purchasing farmland

Renting can be an integral component of a business's strategic plan when aiming to expand its land base and grow operations. To compare any cash flow advantages of cash rental agreements versus purchasing land, we subtract the costs of land rental from new land purchase costs, assuming a 25% downpayment and a 25-year amortization (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Based on the province-wide RP ratio, the cash flow benefits of renting versus buying can vary significantly across different regions.

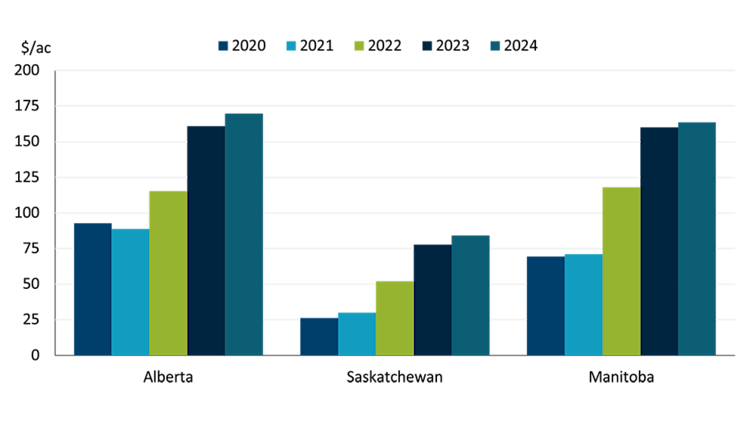

As the 2024 RP ratio in the Prairies remained stable, the cash flow advantage of renting land increased slightly compared to purchasing. The increase ranged from $5 to $10 per acre, influenced by lower interest rates that helped offset some of the rise in farmland values related to newly purchased land payments (Figure 1). Since 2020, Alberta's rent advantage increased by $77 per acre, Saskatchewan's by $58 per acre, and Manitoba's by $95 per acre.

Figure 1: Per acre difference in profitability for renting vs newly purchased land in the Prairies

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC

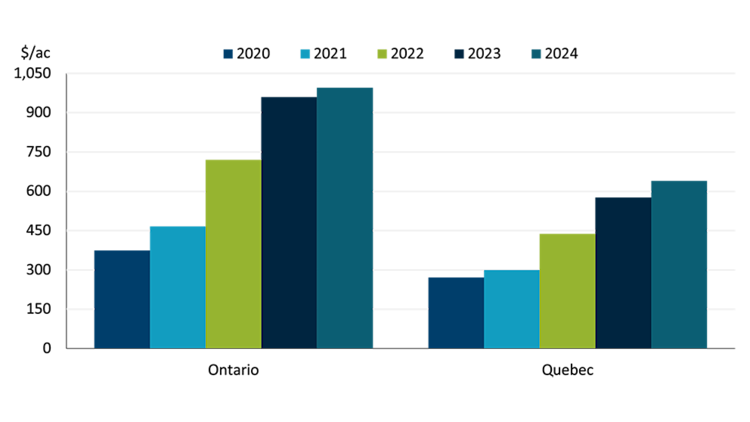

Ontario and Quebec producers have also experienced better cash flow with rental agreements than purchasing land. From 2020 to 2024, Ontario's rent advantage increased by $620 per acre, and Quebec's by $368 per acre (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Per acre difference in profitability for renting vs newly purchased land in Ontario and Quebec

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC

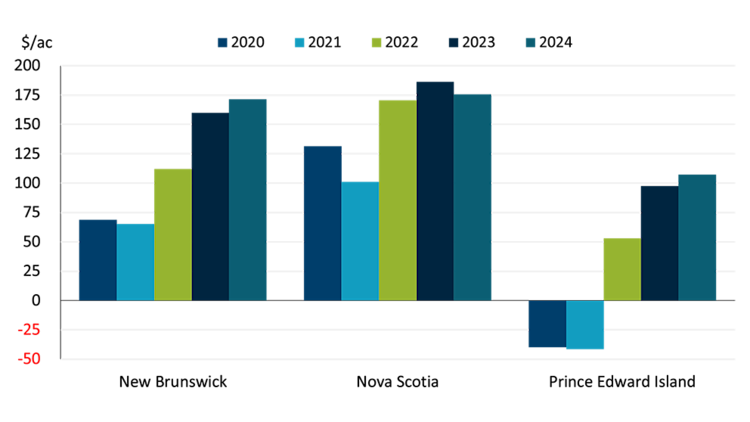

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia have seen improved cash flow from rental agreements compared to land purchases (Figure 3). From 2020 to 2024, New Brunswick's rent advantage rose by $103 per acre, while Nova Scotia's increased by $44 per acre, the lowest growth in Canada. In 2020, Prince Edward Island (PEI) producers experienced better cash flow from purchasing land over renting, the only region in the country. The RP ratio in PEI has dropped the most in Canada over the last 5 years due to rental market adjustments, which improved the cash flow advantage for renting by $147 per acre.

Figure 3: Per acre difference in profitability for renting vs newly purchased land in Atlantic Canada

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC

Despite the advantages of improved cash flow by renting in 2024, it is always prudent to carefully evaluate production costs before entering into new land rental agreements to fulfil operational requirements.

Purchased land appreciation since 2020 highlights benefits to owning

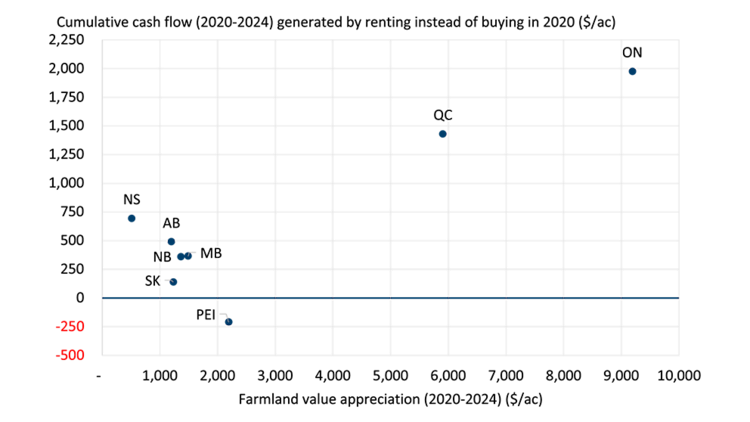

The previous charts have demonstrated the annual cash flow advantages of renting farmland in recent years compared to purchasing. However, this analysis does not account for one of the major benefits of purchasing, namely land value appreciation. With the RP ratio data history available, we can compare purchasing versus renting in 2020 and the impacts on cash flow against land appreciation over five years. For simplicity, we will assume that the rental rate was fixed for five years at the 2020 rate, the purchased land was locked in for the same period, and additional cash flow generated was capitalized at the 10-year Canadian bond rate.

Renting land has been more advantageous for cash flow relative to purchasing in all provinces except Prince Edward Island (Figure 4). Saskatchewan producers gained $140 of additional cash flow per acre over five years, Alberta $490 per acre, Manitoba $365 per acre, Quebec $1,430 per acre, and Ontario $1,975 per acre by renting vs purchasing in 2020. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick also saw rental advantages. In PEI, purchasing land in 2020 actually led to a higher annual cash flow due to the highest rental rates in the country at that time. Consequently, opting to rent in 2020 would have resulted in a cumulative cash flow of -$210 per acre compared to purchasing.

Figure 4: Looking back at choosing to buy or rent farmland in 2020 related to cash flow and farmland value appreciation

Sources: Statistics Canada, FCC

On the other hand, if an operation had bought land in 2020, it would have experienced increases in land values. For example, in the Prairies, farmland increased $1,200 to $1,500 an acre (Figure 4). In Central Canada, land values have gone up more dramatically since 2020 with Quebec farmland values growing nearly $6,000 and Ontario increasing nearly $9,200 on average. In the Maritimes, that growth ranges from $500 in Nova Scotia to $2,200 in Prince Edward Island.

Bottom line

The choice between renting and buying farmland depends on various factors, such as comparing the cash flow benefits typically associated with renting to the asset appreciation demonstrated by the notable rise in farmland values nationwide. As producers evaluate their options, they must consider their unique financial situations and future expectations for rental rates and farmland values, ultimately balancing short-term profitability with long-term asset growth.

Lyne Michaud, É.A., Manager, Valuations

Justin Shepherd, Senior Economist