Turning trade disruptions into opportunity for Canadian pork

Today’s post draws from our recently released report Navigating Trade Disruptions and Volatility. The first post examined the global performance and diversity of Canadian ag and agri-food exports, and a second focused on trade tensions, volatility and Canadian oilseed exports.

Tariffs on U.S. pork exports to China and Mexico resulted in weaker prices in the U.S. hog and pork supply chain. Markets have rebounded, largely on the expectation that the African Swine Fever outbreak in Europe and China will lead to a surge in pork import demand.

Historically, Canadian pork exports fall when volatility climbs. Yet the export response within individual key markets differed. Market share, distance to market and trade relationships are all factors that impact the response of exports to current volatility spells.

Diversifying pork export markets is an opportunity

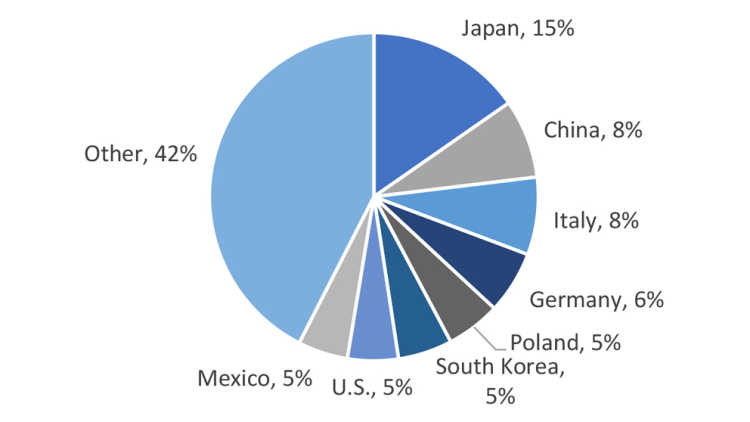

Canada was the fifth largest pork exporting country in 2017 behind Germany, the U.S., Spain and Denmark. The U.S. and Germany are also dominant importing countries (figure 1). Canadian pork exports match global import patterns, but are quite concentrated: the U.S., China and Japan purchased over 80% of Canada’s pork exports in 2017.

China has been a growing market due to rising incomes and a smaller hog herd, with Canadian pork sent there increasing 161% between 2012 and 2017. Europe represents a large import market that can expand for Canadian pork under CETA. Implementation of CPTPP will make Canada even more competitive in the lucrative Japanese market and other Asian destinations, especially considering European and American exporters will not enjoy the same market access privileges.

Figure 1. Market share of leading pork importing countries, 2017

Source: UN Comtrade database

Volatility harms pork export prospects

Tariffs raise the purchase price for importers and/or lower the price exporters obtain, leading buyers and sellers to postpone or cancel transactions. In the current environment, this means lower U.S. pork export volumes and additional Canadian export sales. However, these changes in supply and demand conditions lead to price swings, which can weaken trade flows over the long term.

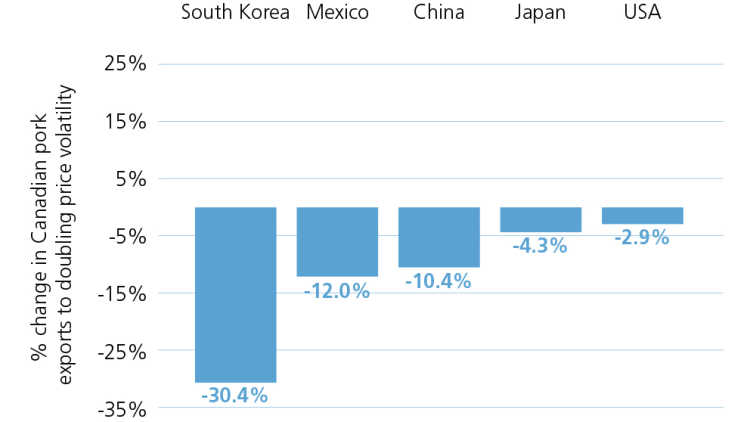

Historical data on bilateral pork trade flows show that Canadian export responses to volatility (measured over 12-months) were widely different across markets. Changes ranged from a small drop of 2.9% in our exports to the U.S. when price volatility doubles to a drop of almost one-third (30.4%) in exports to South Korea (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Canadian pork exporters see varied response to price volatility

Source: CIMT, FCC computations

The largest pork importing country (Japan) is also our most important export market. Its size and our market share mean our trade relationship is solid and almost immune to small bouts of price volatility. The U.S. is our second most important destination. Their proximity, coupled with the influence of the U.S. hog market on the Canadian hog and pork supply chain, mean volatility has little impact on trade flows. Exports to smaller markets like South Korea and Mexico respond more strongly to volatility.

Overcoming volatility to maintain leadership in global markets

Volatility means prices swing up and down. Import tariffs can draw a wedge between pork products from different origins (Canada and the U.S., for example) that otherwise would be priced very closely. That’s a short-term opportunity which can turn into a long-term gain in the presence of strong and stable market access provisions from recent trade agreements.

Jean-Philippe (J.P.) Gervais

Executive Vice President, Strategy and Impact and Chief Economist

J.P. Gervais is Executive Vice President, Strategy and Impact and Chief Economist at FCC. His insights help guide FCC strategy, monitor risks and identify opportunities in the economic environment. In addition to acting as an FCC spokesperson on economic matters, J.P. provides commentary on the agriculture and food industry through videos and the FCC Economics blog.

Prior to joining FCC in 2010, J.P. was a professor of agricultural economics at North Carolina State University and Laval University. J.P. is a Fellow of the Canadian Agricultural Economics Society. He obtained his PhD in economics from Iowa State University in 1999.